AUDIO

Growing up in Lima, Peru, I fell in love with music through salsa and Afro-Peruvian rhythms that shaped my childhood. When I moved to Southern California in the early 80s, hip-hop captured my imagination. I still remember hearing KDAY’s legendary Mixes for the first time in 1984—Dr. Dre, DJ Yella, and the Mixmasters layering hit after hit, blends, cuts, and scratches into something new, innovative, and fresh, and I was blown away by it!

The audio compositions here are my tribute to those mixes, and that golden era of rap. I hope I’ve done them justice.

Enjoy

-5:37

All audio found here is dated: 2003 – present

DEAD BODIES

Dead Bodies – ‡

Wanna see a dead body?

READY TO DIE

Ready to die – ‡

made a mix just for kix and you’ll be on our –

and oh yes there’s a highlight to the show of course, to hear d.j. les la rock go off! go off!

ZERO

zERO – ‡

eyes wide mixed

INTERLUDE NO.5 IN A SERIES OF 37

INTERLUDE NO.5 IN A SERIES OF 37 – ‡

just a quickie.

なに?

matthew 5:37

matthew 5:37 – ‡

All you need to say is simply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; anything beyond this comes from the evil one.

Boom Bap Original Rap

2THE1EYELove

2THE1EYELove – ‡

This is dedicated to the one i love. HIP HOP BODY ROCK DOING THE DO

put it on

put it on – ‡

Some boys see me gun nozzle and take a we fi joke

Boy, you gwan dead before you see me gun smoke

See me gun nozzle and take me fi joke

You gwan dead from a me you provoke

Jig-A-Low (jig jig a low)

JIg-A-Low (jig jig a low) – ‡

fly like a dove, and come from up above.

an amalgamation of many of the sounds I personally find to be rated: DEF. pure uncut intravenous golden era in your blood system. forever.

Deepspace

Deepspace – ‡

“bobby, who’s the greatest man in america?”

“i don’t know? the spaceman i guess?”

I travel to the ends of the universe and beyond

CHAMBERS

chambers – ‡

enter the chamber, and it’s a whole different sound

A small sampling of some of my favorite Wu-Tang songs over classic golden era rap.

semantics (many many styles, this one i chose to choose)

semantics (many many styles, this one i chose to choose) – ‡

it’s another one of them ole funky 537 things unowudimsayin?

ROCKETINTHEPOCKET

ROCKETINTHEPOCKET – ‡

got a rock, rocket in the pocket.

1580 ALLDAY

1580 ALLDAY – ‡

pass the peas like they used to say

aBOUT MY MUSIC

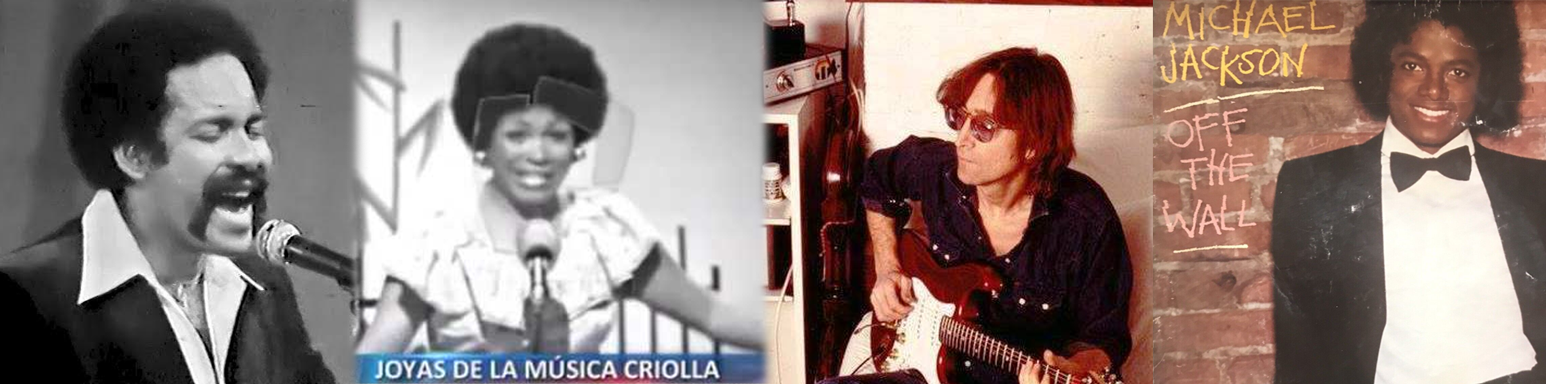

Growing up in lima, Peru in the 1970s, I was exposed to a wide variety of music, particularly salsa, música criolla, which included Afro-Peruvian rhythms, a favorite of my grandma’s brothers and sisters, and whatever popular American music came to us through movies, radio, and TV. I clearly remember hearing the Bee Gees, ABBA, John Lennon’s “(Just Like) Starting Over,” Michael Jackson, and others. Still, the one constant was salsa, which dominated as the soundtrack of my early childhood.

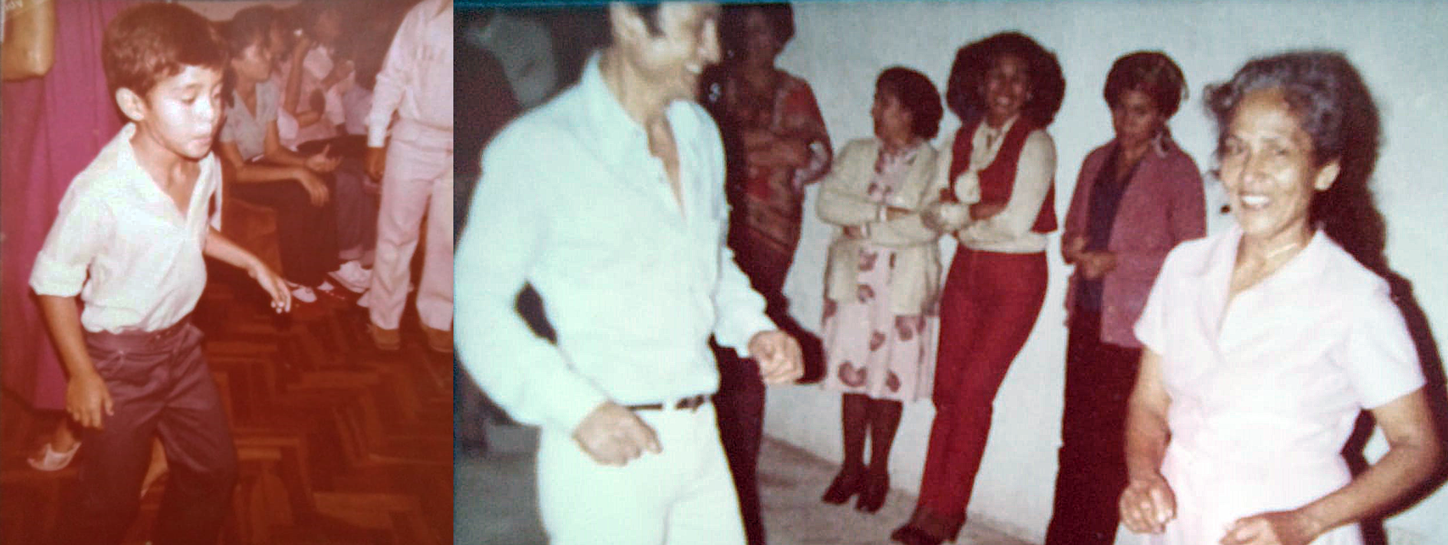

With a large family of uncles and cousins and never-ending reasons to celebrate, life was never without sound, and music was a major part of that. Dancing played an equally significant role in my life in Peru, as it was common to see the older uncles and their girlfriends dancing—and for us kids to join in as well. Salsa dancing was the definition of cool, and it was incredible to witness the entire living room filled with my aunts, cousins, and uncles, all dancing to the latest salsa hits blaring through the speakers. Even the older relatives got a chance to dance to more traditional Lima-style music, like valses criollos, while the rest of us watched, clapping and cheering them on.

1981

Upon my arrival in Southern California in 1981, the music I was exposed to changed drastically. Salsa, which had been a constant presence in Peru, was now mostly played at infrequent family gatherings, as my family here lived hours apart, spread throughout Los Angeles. It was no longer as persistent or all-encompassing as it once was back in Peru. Instead, I discovered new sounds through the car radio—a novel experience for me at the time, as even being in a car itself was something new. On the radio, I heard Top 40 hits, classic rock, and occasionally, through 8-tracks, some Spanish ballads by artists like Camilo Sesto and Juan Gabriel, as well as the music of Elvis and Tom Jones. Salsa still played, but only at the once- or twice-yearly gatherings, and usually late into the night when most of us kids were trying to sleep.

Through one of my uncles, who was closest to me in age, I was introduced to the Beatles, Ozzy Osbourne, the Beach Boys, Pink Floyd, and more.

I didn’t yet have a sense of my own musical taste. None of the music I heard truly moved me—not like salsa, which made me want to dance or tap out rhythms on a table. It was mostly just cool tunes playing in the background. If I had to name a favorite group before I turned ten, it would have been Van Halen—partly because I heard their music a lot, but also because their sound was, and still is, incredible.

an Impromptu dance leads to a life altering discovery

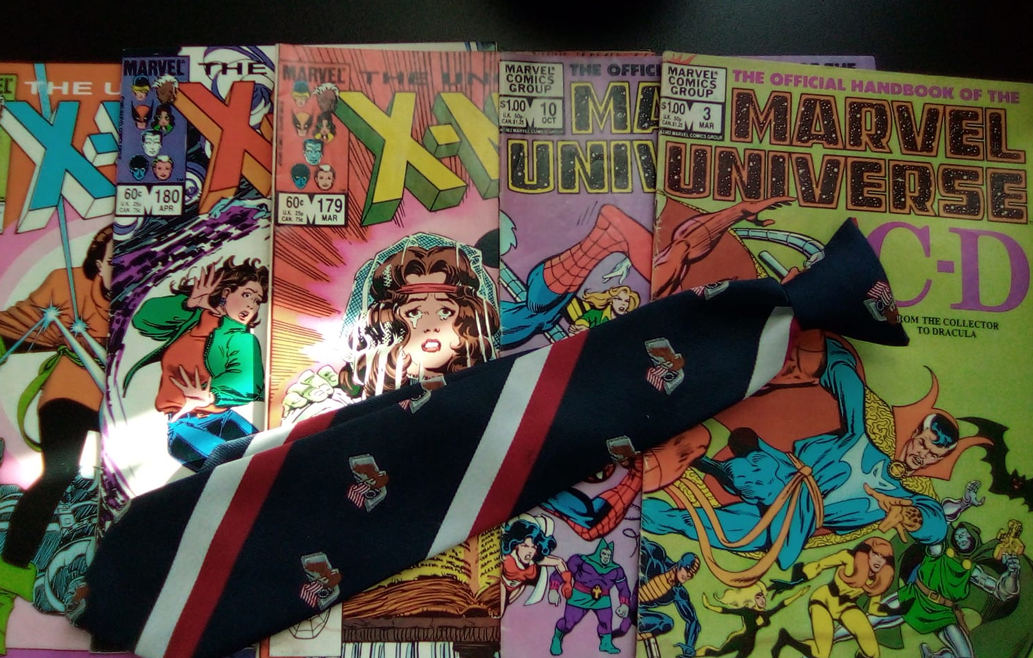

During the 1982 school year, I attended a private Baptist school—the kind where memorizing Bible verses was part of the weekly grade, and the uniform dress code required dress shoes and a tie. The school was located inside a large church, which included a chapel and classrooms situated along its sides. It housed all grades, from first grade to senior year, within a single building, bringing together about 200 children of all ages in mixed classes for the entire school year.

That year, I befriended a classmate and one of his friends, a boy with the last name “Lewis,” who was a few grades above us. The three of us bonded over a shared love of Marvel comics, and most of our conversations revolved around that topic.

1983

On the last day of school, as the final bell rang, I made my way out, past the lingering kids in the hallway, toward the swinging exit doors that led to the outdoor parking lot, which doubled as our gated playground and lunch area.

The scene is still vivid in my mind: the bright, early June sunshine streaming through the double doors into the dim hallway. Once outside, immediately to my left, a crowd had gathered. A circle of about 15 kids stood transfixed by something happening at its center. Curious, I quickly made my way over to see what had captured everyone’s attention.

In the middle of the circle was Lewis. He was popping his arms in a wave-like motion, letting the movement ripple through his body from his right arm to his left. As the wave left his body, he pointed to another boy in the circle—a younger kid I recognized by name because it was so unique. This boy, a year or two younger than me, stepped forward and began performing his own version of the wave. His movements were distinct from Lewis’s but equally mesmerizing.

Although no music was playing (a sacrilege in that setting!), the boy began singing the chorus of a popular Pointer Sisters song. “Aaaautooomatic,” he sang, letting the melody guide his movements as he sent the wave through his body and back out again.

I was in awe of what I was witnessing. Something stirred deep within me—a memory I hadn’t thought of since leaving Peru. I recalled being in a dance contest held inside a small corner restaurant there just a few years earlier. My cousin and I had practiced a dance called El Robotito (“The Little Robot”), which featured stiff, robotic movements reminiscent of a mime. We were inspired by watching Michael Jackson perform the robot dance on TV and we even wore makeshift costumes to complete the act.

In the end, we placed second, losing to a kid who performed a more traditional Peruvian dance in full traditional costume—and who happened to be the niece of the restaurant owner hosting the contest. We took home a rotisserie chicken as our prize, but what stayed with me was the reaction on the faces of the neighborhood kids who watched us perform, a mix of wonder, awe, and curiosity. For most of them, it was the first time they had seen anything like that in person. For me, it was the first time seeing strangers react to my dancing, and their favorable reactions filled me with pride.

1580 KDAY

As Lewis and the other kid danced, I felt an overwhelming desire to understand what I had just witnessed. It was unlike anything I had ever seen, but I knew it was a dance—and dancing required music. After the two stopped and the crowd began to disperse, I approached Lewis, bombarding him with questions. One exchange, in particular, remains crystal clear in my memory:

“What kind of music do you listen to when you do that dance?” I asked.

Lewis replied, “When you go home, put your radio on AM and turn the dial all the way to the right. You’ll know it when you hear it.”

I was instantly hooked. Run-D.M.C., Whodini, Kurtis Blow—all the hottest rappers of the time played in heavy rotation for me that summer. Their music felt accessible. You didn’t have to be a rock-and-roll god to belt out a song; you could just talk—but in a slick and clever way. From that day forward, I kept my dial locked to that station until it eventually changed formats sometime in 1991.

Something about the early New York beats and scratches captivated me instantly. The rapper’s words and wordplay struck me as clever—a quick, witty, streetwise attitude that reminded me of Peruvian street smarts and the sharp humor I’d grown up with. We call that quality mosca. The phrase ponte mosca, which literally translates to “become fly,” doesn’t make much sense in English, but metaphorically, it means to stay sharp or alert, like a housefly’s quick and perceptive movements. This music felt exactly like that. The attitude coming from the rappers embodied it too—fast, clever, and alive. The way the rappers juggled their words with the beats and scratches over a simple yet funky and catchy rhythm was like nothing I had ever heard and, at the same time, eerily familiar. It wasn’t my parents’ music, my uncles’ music, or what was playing on the car radio. It was mine, and I’d discovered it by chance.

I was drawn to the simplicity of the drums, the almost tongue-twister way of the wordplay, and especially the scratch. One of the first tracks that caught my attention on all those levels was Run-D.M.C.’s “Here We Go.” There was something so raw and dangerous about Billy Squier’s “Big Beat” drum being cut up by Jam Master Jay. The fact that it was live—I could hear the crowd—it sounded like a séance to wake up the hip Hop body rock ghosts. There was something so confident, so sure, about how Run and D.M.C. rhymed over the beat. The curse word at 2:23 (bleeped for the radio, of course) was scandalous at the time. But that zigga zigga zigga scratch from JMJ had me hypnotized.

Another track that immediately stood out to me was “Stick ’Em” by the Fat Boys. The pattern of Buffy’s beatbox, combined with the way Markie Dee and Kool Rock-Ski’s rhymes rode the beat, was the very definition of cool to eleven-year-old me. The scratch in that song was mesmerizing, and I quickly recognized it, as well as Buffy’s beat patterns as fundamental elements of hip-hop.

To me, Those patterns seemed to extend beyond the music—they mirrored the arrows and shapes of graffiti letters, the footwork of breakdancers, and, of course, the lyrical flows coming through the radio. It was all interconnected—funky, dope patterns that felt like pieces of the same larger puzzle.

Looking back, I realize that even in this new genre, there was a familiar sound and soul to the music: the African drums. Whether in the salsa, or música criolla that flooded my early life or the rap breaks that came later, they were like threads connecting the rhythms of my childhood to this new world. Hip-hop offered a cultural and emotional bridge to my past, to my time in Peru that was filled with dance and the never ending sound of the drums.

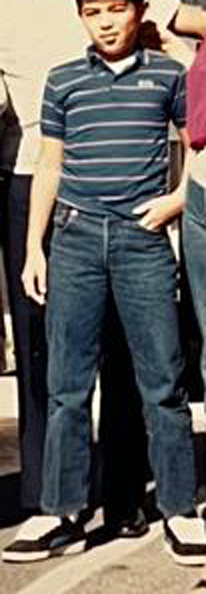

1986-

Around this time, I was fully immersed in hip-hop, decked out in Pumas and Le Tigres, fresh off the breakdancing craze, and since I already loved drawing, diving straight into graffiti. The soundtrack of my life was whatever KDAY was playing.

Although KDAY played scratch mixes by dr. dre and dj yella as early as 1984, where they would play an instrumental such as roxanne, roxanne by UTFO, and scratch along with it, blending into another song after the first had played on, It Wasn’t until sometime in ’86 that I first remember hearing the Mega Mixes. These consisted of multiple songs and scratches played back to back, a never ending carousel of pure dopeness, which continue to inspire the mixes I create today. I believe the first DJs behind these mixes were Dr. Dre and DJ Yella. They crafted intricate compositions using the rap hits of the moment, expertly layered—sometimes with up to three tracks playing simultaneously, all in perfect synchronicity. These mixes often featured exclusive records from their own artists and world premieres from others. Later, DJs like Tony G, Gemini, Joe Cooley, and the rest of the original KDAY Mixmasters took over.

The Friday night mixes were like an auditory feast—a buffet of hit after hit that lasted for hours, starting as early as 4:30 in the afternoon and going well past midnight. They were filled with scratches, interludes, and seamless transitions from one dope song to the next. If a single song from this era, like “Eric B. Is President” by Eric B. & Rakim or Biz Markie’s “Make the Music with Your Mouth, Biz,” could have me rewinding my cassette a hundred times, then an entire mix packed with back-to-back hits of this caliber had me in hip-hop heaven.

While my musical tastes now span a wide array of genres, the music of my formative years—the golden era of rap—will always hold a special place in my heart. It was my first love, and its influence continues to guide my creative journey to this day.

-5:37